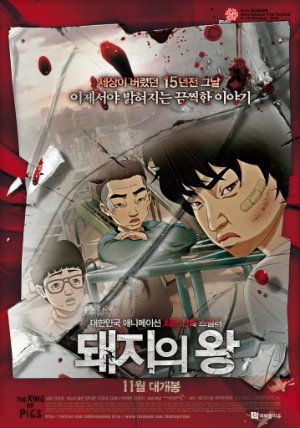

If you’ve ever read a review of a Korean film by me or anyone else, there is a good chance social commentary works its way into the picture somehow. Rarely does an action or drama come along that doesn’t incorporate something critical to say about the institutions in place or the way people treat one another. Perhaps this is why it has a voice commanding so much attention among film enthusiasts worldwide. Yet rare is the film that so completely serves as a statement of social commentary as The King of Pigs. The first feature film by Yeun Sang-Ho, The King of Pigs is an animated tale that rips the lid off of a system of abuse reportedly common in South Korea’s jr. high schools.

The King of Pigs is a thoroughly independent production. It comes after only directing animated shorts prior to it and according to Yeun in an interview I did with him, he started working on it before receiving any funding, only later receiving a 100,000 dollar grant from a company that invests in independent films. Most of those involved in the film’s production, including the voice actors, are from among the directors friends. He describes how he worked with Yang Ik-June and Kim Kkobi (familiar to many from their work together on the film Breathless) because he “had talked to them a lot about this film beforehand....It was more of a collaboration for fun rather than calling it casting.”

It begins in an almost impossibly bleak place: a woman lies dead, strangled, as a distraught man trembles in a shower. The bespectacled man, calmer now, receives a call from an investigator with the contact information of a former classmate whom he quickly makes arrangements to meet. That man is Jong-Suk, a freelance writer stuck in a clearly unfulfilling assignment. Distrustful, or just filled with pent up rage, he lashes out physically against his live-in companion after she returns home late without returning his phone calls. As low and damaged a state the two former school friends find each other in, signs point to an even darker past, which comes up through episodes they recount in one particularly tragic jr. high school year. It offers insight into the roads that may have led them to these malcontent grown up lives, and is the first of many allusions to continuous cycles of violence and despair.

Flashbacks show an all boy school as a frightening place for many, who are subject to the whim of a few. Classroom ‘managers’ taunt and order around the more meek students in the class, giving approval to certain acts of bullying while menacing others for their lack of seriousness in their studies. They do this under the watchful eye of an upperclassman who beats them should they fail to maintain a positive environment in the classroom,and he in turn reports to an older student who is something of a leader in the school government. This hierarchy of overreaching control is not made up of embittered underachievers or those who are victims of abuse themselves. Rather, these members of the school community appear to be economically advantaged. As a result, they also experience academic success making for a reinforced achievement for some while for the majority, failure perpetuates itself. An incensing scene finds the class monitors tormenting a talented boy to the point that he relinquishes a venerable spot in a writing competition to one that is accustomed to receiving every accolade. adults are eerily absent from the picture or at best very slight in their influence.

Jong-Suk perceives these different types as dogs and pigs. The dogs growl menacingly and control what goes on while throwing scraps to the pigs who can only hope to have occasional kindesses bestowed upon them instead of the usual abuse. As if in answer to the state of fear these students live in, another crucial character, Chul, appears.

Chul’s homelife is the most unstable and perhaps as a result he is reckless enough to defy the bullies. While another key figure, Chan-young (the same whose opportunity to enter a writing contest was dashed) tries to escape the fate of the pigs by putting his head down and trying to outlast the abuses of the class managers, Chul matches violence with even worse aggression. His message is not that of taking a higher road, but rather one of becoming a bigger beast than those who would behave monstrously. Despite his scary demeanor, he represents a fighting resistance against those in power to Jong-Suk and Kyung-Min. And yet, his propensity for greater violence brings adult authority down on him and leads to confrontation with the highest level of students running the show. The only act left for him to conceive of that could make a difference for the three is so desperate and fatal an idea, it seems destined to fall into ruin.

Meanwhile, the causes for such disparity between students are shown to extend beyond the confines of the classroom. In the young Jong-suk’s family home, his sister throws tantrums about her lack of up to date goods that others around her enjoyed. She even turns to theft to compensate her frustrations, which are amplified by a status-obsessed society. Students speak of the long stints of time they go through without being able to afford to eat meat. In a poignant exchange, Kyung-Min finds his father, an only relatively prosperous owner of a karaoke bar and the elicit prostitution that takes place there, violently casting out Chul’s mother, whose impoverished state forces her to take on this undesirable work. Chul is there too, ready to strike out to defend his mother, but the sight of Kyung-min causes him to leave in despondency. It shows how even their bond of solidarity in class is tainted by the venomous relationships that have long been poisoned by want and squalor.

While animation brings to mind fantasy, there are strikingly realistic aspects of this story. Instances of bullying, like when those that wield influence question an individual’s sexuality threateningly for failing to abide established fashion codes, will seem familiar to anyone who’s experienced or been around others who have experienced middle school taunts. Also resonating a recognizable truth is the way bullies conspire to administer sly cruelties until the put upon individual finally lashes out in more serious violence, only then bringing the attention of adult authorities to come down on the one who had been victimized. Perhaps this great realism owes to the fact that, according to Yeun in our interview, “individual episodes in the film are based on (his) experiences” although “structure wise the (story) is pretty much fictional.”

Animation then serves to drive some of the cruel aspects of the story home vibrantly, if not exactly entertainingly. There are fantastical transformation sequences: humans transform into dogs and swines to represent their status. Chul, a boy from whom violence is inseparable from existence, warps into pitch black monstrous forms to show his increasingly hate-filled state of mind. Sequences of a wild eyed cackling feline (perhaps meant to be viewed as the spirit of a cat that was killed in a ritual of brutality) and corpses of deceased family members taunt Jong-Suk, showing the tortured states of mind they are in over their powerlessness in the face of more well-off bullies.

The look of animation also suits the fable-ish nature of the story with its animal-based allegory on haves and have-nots. In fact Yeun claims being a fan of all types of animation including Disney. Chul’s sudden appearance and ability to vanquish the villainous tormentors in the class makes him a mythic figure. Yet, fantasy comes crashing into depressing reality. His heroism comes from a dark place, one brought about by earthly hardships of family tragedy and economic plight. This along with the social politics of school life prove insurmountable.

As Jong-Suk and Kyung-Min continue to recall their harrowing younger days, it becomes clear they are skirting around something. A tragedy with jolting and fearsome connotations will come to light, revealing opens wounds that have never been healed.

The movie may be considerably remarkable movie fans in the West where relatively few South Korean films on this subject have surfaced. In fact they are out there. Yeun mentioned over movies that take on the subject of school bullying, such as Our Twisted Hero. His film stands out, however, as Yeun “didn’t want to fall into that kind of convention, but instead look at (the issue) from a different perspective.”

The lack of simplicity, of an easy to follow struggle between clearly defined hero and villains, helps make it a powerful vision. It also reflects Yeun’s views on the real-life problem. When asked, for instance, about the lack of adult presence, he answered: “In Korea parents really do work a lot. They don’t have much time to spend with kids. I think it’s more of the Society’s problem, not the parents’ responsibility but the society that drives parents away from the kids and into work.”

In fact the film often straddles a line between genre film and more unconventional project. Setting the film’s dark tones from the outset is an ominous-sounding score. Yeun mentioned how he asked the music director for “the soundtrack to be in genre convention. And also (being) a big fan of the soundtrack of Twin Peaks by David Lynch wanted something similar to that.”

While offering little in the way of solutions or hope, The King of Pigs is a piercing beacon shining light on a situation that should be looked upon rather than left to fester in the darkness.

No comments:

Post a Comment