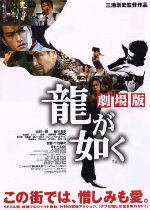

After flooring audiences with OUTRAGE a Yakuza film that walked a fine line between traditional gangster tale and modern, perhaps even critically aware, storytelling, Takeshi Kitano has returned to take things a step further with followup OUTRAGE: BEYOND. I had the good fortune to get an early look at this second chapter when it was included in a select but powerful Midnight Movie sidebar in this year’s New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. Should the series extend to a third installment, which I highly anticipate being the case, this may very well be series’ ‘Empire (Strikes Back),’ a more somber, downbeat followup to its action-packed precursor.

After flooring audiences with OUTRAGE a Yakuza film that walked a fine line between traditional gangster tale and modern, perhaps even critically aware, storytelling, Takeshi Kitano has returned to take things a step further with followup OUTRAGE: BEYOND. I had the good fortune to get an early look at this second chapter when it was included in a select but powerful Midnight Movie sidebar in this year’s New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. Should the series extend to a third installment, which I highly anticipate being the case, this may very well be series’ ‘Empire (Strikes Back),’ a more somber, downbeat followup to its action-packed precursor.

But don’t be mistaken; the first OUTRAGE is nothing less than grim. It took viewers on a deliberately paced tour of shady deals, heated arguments, and acts of intimidation, all adhering to a code with an inner logic nearly impossible for outsiders to fully comprehend. The further the film progressed, acts of violence became more frequent and more brutal, particularly those carried out against Otomo (played by Kitano) and his gang, the Otomo group, whose prowess made them both a weapon and a target of the most powerful Sanno Kai Yakuza clan. As each member fell like dominoes, those waiting for a burst of retaliation would be left cold. The string of violence was presented in bleak business-like fashion, with one betrayal leading to another to another until a new regime would be left calling shots from the inner circle.

The violence here is also colder, more functional. There are less of the morbidly inventive, cringe inducing scenes of violence that pepper the first movie (though a few will brand themselves upon the brain, one of particular nastiness involving a batting range). But they are just as savage. This serves to breathe an even greater sense of realism and for that it is all the more ominous.

Part 2 also arguably trims some of the fat found in the first movie. Take for instance, its segments where the Otomo group tricks and blackmails an African diplomat into doing their bidding and essentially being under their thumb. They may add some humor and may even be based on real life events. But for the most part, they distract from the rising tensions between the various players as they jockey for positions of power. There is nothing like that in ‘BEYOND. Instead it maintains a sustained note of dread and build up to the grisly fates that await much of the cast.

Without a doubt, Keiichi Suzuki’s ice cold original soundtrack score drives home this sense of uneasiness. Used to even greater effect than in the first Outrage, it feels as though it could have been lifted from an ‘80s horror film. It will no doubt tickle the fancy of those who appreciated the retro leaning soundtracks of films like Drive and Beyond the Black Rainbow.

If the first Outrage was an elegy on disloyalty, then Outrage: Beyond is a steely eyed vision of comeuppance, the wheel of karma turning to crush those who would discard honor to feed one’s own greedy ambitions. This could not have been made any clearer than in the film’s startlingly abrupt, head on conclusion. Characters, both new and familiar from the first film are faced with the seeds sown by their treachery, as all the while a new power structure is brought into the picture in the form of a rival criminal organization based in Osaka.

As before, Otomo stands out as an anomaly. Dirt in the eye of the established power structures, causing them to rub and scratch in irritation. Unlike the first film, where this was caused by his over the top viciousness and flouting of typical mobster ambition, ‘BEYOND finds an Otomo that is weary of the game and unwilling to play the pawn-like role other powers that be have in mind for him. He is introduced into the sequel, having been believed to be dead after a vicious stabbing, being released from prison early. This arrangement is made by returning police officer specializing in organized crime Kataoka, whose plans for Otomo are no less manipulative or acidic than the criminal organizations rankled by the fact of his existence. He hopes that Otomo’s release will lead him to lash out against those forces that had led to his downfall, as well as those who are vying for control of the local crime syndicates. Otomo has other ideas on his mind, though.

The shifty cop Kataoka has a more prominent role than in the first OUTRAGE. He and other returning characters, as well as a few new ones have caricature-like personas that would fit perfectly into a Coen Brothers film. Standing out most, perhaps, are the Osaka-based crime boss Fuse’s two right hand men, Nishino and Nakata. The intensity of their pronounced speech as they bully about those that come before Fuse has an offbeat comedic element, something that is probably a hallmark of Kitano being at the helm of the production.

Also noteworthy is the stark absence of female roles in the film (the poster above gives an accurate sense of this). Even the first had very few women, and then they were placed in only the most cursory supporting roles. But I do not think I would be off in my estimation that female characters have less than a minute total onscreen time in ‘BEYOND. Here it is as if Kitano wants to increase the authenticity of his product. This Yakuza world is ruled and kept running by old, provincial men and, like it or not, that is exactly what we are getting with Kitano’s film. Or perhaps it is an insistence on distilling only the most essential components of this karmic tale. This stands in contrast to a vast collection of Yakuza tales directed by Takashi Miike, whose films include female characters as little more than victims and sexual objects, yet do little to evoke empathy or call for a critical look at the situation.

A standout feature of both OUTRAGE films, but especially ‘BEYOND, is that they in no way glamorize this violent lifestyle or make it seem cool. Not even a little. Those in power are calculating, lacking in empathy, and seem immobile, as if they’ve burrowed themselves into their powerful seats and are too set in their ways, or fearful of their downfall, to move. At the outset Kato (usurper of the Sanno Kai) and his number two, Ishihara (who betrayed the Otomo group in the first film) in control, the direct result of their double crossing transgressions in OUTRAGE’s conclusion. Any so-called honor or respect goes out the window as they are shown putting the older members of the group on notice: if they do not get with the times and learn the ways of the modern (re: economic) con, their days are numbered. It adds an interesting theme of generational conflict to the already blackened vision of a landscape where there is virtually no honor amongst thieves.

With this festival screening coming right around the same time as the film’s native Japanese release date, there is no telling its future quite yet. Let’s hope the success of the first film and fresh take on a classic genre will add some speed to OUTRAGE BEYOND’s path toward these shores.

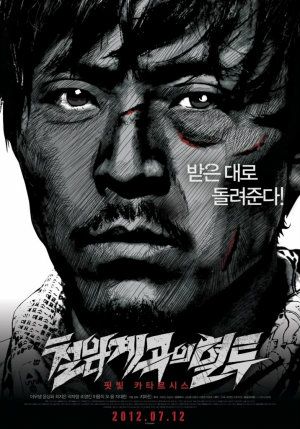

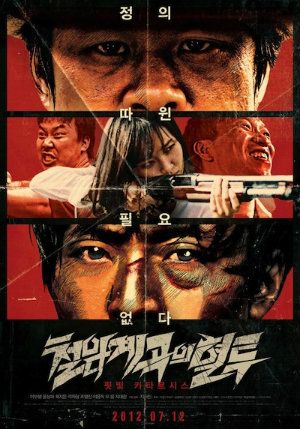

During the summer, with images from the New York Asian Film Festival still seared into my brain, I hoped to learn more about one of the festival's less heralded yet highly impressionable films BLOODY FIGHT IN IRON ROCK VALLEY. Shot on a shoestring budget, it's a modern take on the classic Western with a main protagonist driven by revenge (reviewed here). I sought out an interview with the South Korean film's newcomer director JI Ha-Jean. He graciously answered my questions via email, giving thorough insight into his vision and the trials of making a low budget action film.

Q: I have come across many independent films from South Korea that are dramas or horror films, but not so many action. Bloody Fight In Iron Rock Valley is a very skillfully made action film. What drew you to making a feature in this genre?

JI Ha-Jean: Personally I love Western and Crime movies. I especially like the directors Sergio Leone and Jean-Pierre Melville, so I made my film with the idea of learning and practicing their cinematographic heritages in mind.

I decided to make this film after reading the book ‘Rebel without a Crew: Or How a 23-Year-Old Filmmaker With $7,000 Became a Hollywood Player’ by Robert Rodriguez. It’s like the bible of making action films with a micro budget. The reason I chose the Western genre especially is that it suits low budget filmmaking. Following the simple rule, which is ‘a mysterious man visits an isolated village and wipes out all the bad people,’ and shooting well crafted minimal action scenes, I expected the film to come out great even though it was made on a very low budget.

Q: Considering the minimal budget you had to shoot on, were there concessions or improvisations to your plans that you knew you would have to make before shooting started?

JH: The costumes were the hardest part. The extra pieces of clothing are very important for making this kind of movie, in which 17 people die, and most characters get injured or are intensely chased. However, we didn’t have a big enough budget for all the costumes, so most of the characters wore only one outfit until the end of shooting. So I tried to shoot the film in sequential order, but it was difficult. You might have noticed that, repeatedly, characters’ clothes are dirty and later changed to clean; torn and later they look like new. Also, I had to lower my expectations for the blood explosion scenes. There was only one chance, so even though I was not fully satisfied with it, I had to say OK.

At last, we had to finish the shooting within 25 days, so we were always in a rush. We had to revise lots of scenes in order to shoot the action sequences. Especially for the scene where the character ‘AX’ is killed, it was a very complicated scene using wire action, but we finished it within 3 hours. We had to give up lots of details that were in the original plan.

However, with this restriction, the making of the film had a more frenetic vibe, so I think it is not too bad.

Q: I’ve read that it took something like 2 months to shoot the movie -- incredibly fast! How did you make that happen?

Q: I’ve read that it took something like 2 months to shoot the movie -- incredibly fast! How did you make that happen?

JH: I will correct you here; it took just 1 month! It was very important for the staff and actors to get along with each other well in order to finish the film in such a short period. The shooting was done using hand-held filming techniques without any lights. We were always on stand-by. 100% of the sound was done in post synchronization. Actors were very well aware of each roll’s characteristics.

There was different theme music for each character, which we made before the shooting. We used it while shooting and it was very helpful for the actors to keep their emotions on the spot.

Also we had very few members on the staff. This was also helped to make things go fast. It’s also written about in Rodriguez’s book. The staff was made up of 7 people on site. We were always shorthanded, but they were professionals in their fields, which accelerated the process. Also, we knew very well know what we were going to do. We pursued what we could, and quickly decided to give up what was impossible at that moment.

Q: The time and place that the movie is set does not seem clearly defined. It appears like it could be in the present, but not shown in exact detail. Is it meant to be open to interpretation? Did you have a particular time and place in mind?

JH: There is a particular time in the movie. The main character has been released from prison 12 years after 1998, so the background is in 2010.

However, in general I wanted the time to be not defined. In the films of Kurosawa Kiyoshi or Sergio Leone, the era is not clearly defined. So the story in their films has a universal context beyond the particular era.

Korea’s development has been very fast and highly compressed within the last 60 years after the Korean War. There has always been huge demolition and reconstruction in our history, so the tragic story inside ‘Bloody Fight in Iron-Rock Valley’ is quite common in our society. If the background of this movie was not the mining village in Gangwon province, it would have been difficult to blur the time. Because Korea is changing so fast, the old things are vanishing very quickly. However, the mining village of Gangwon province has stayed the same over decades. If we say it is the 1970s, people can still believe it. You could say another main character of this film is ‘space’, so it was very important to establish the atmosphere of the place.

Q: There is a very interesting use of space, for instance, the gang’s base. It seems like it was created using old machinery, other unusual props. How did you give the space the look you wanted?

JH: We didn’t have enough time or budget for designing the setting more. We had to use the location as it was, so we made a big effort while location hunting. The gang’s base is also shot at the location exactly as we found it. There are many abandoned buildings in Gangwon province. So we believed we would be able to find a great spot after checking places carefully.

After confirming the location, we revised the scenario to be suitable for it. I brought pictures of the places home and adapted the scenario and the characters’ moves to the place’s atmosphere.

Q: Several of the actors in the movie, I’m thinking particularly of LEE Moo-Saeng, YUN Sang-Wha, and CHOI Je-un have a very bold/striking look. How did you go about casting and selecting them for the role? Did they agree to work on the movie right away.

JH: I was very lucky with the casting. There are many great actors in the films of Sergio Leone, Howard Hawks and Sam Peckinpah. In their movies, the actor’s face is the characters itself. I especially like Walter Brennan, Charles Bronson, and Warren Oates.

For the ideas, I tried to find the answers within the actors’ faces. For instance, LEE Moo-saeng, his face is very bold, has a striking appearance and his eyes express quite a gloomy feeling. When I shot extreme close-ups of his eyes, I could see a sad man with a big hurt memory. However, he also looks very strong and restrained.

YUN Sang-hwa looks very violent, but also exhausted from the wrinkles on his face. In the movie, there is only one time his hat is taken off, and that is where he looks the shabbiest. Also, he shows different aspects of his look in the flashback scenes.

CHOI Je-un is a sassy girl working in the gambling house. But she is also a sweet girl, going to her father’s temple every day. Ms. CHOI has a proper look in that aspect. Also she knows how to handle guns very well.

The western genre is very rare in Korean cinema, so most of the actors were intrigued by that. I also persuaded them with my convictions to make a great western film. It helped them to get on board the project.

Q: The movie is notable for action sequences and use of different weapons (a torch, nail gun, shotgun, etc.) Were there any particular influences on directing the action/violence in the movie? Any interesting stories/challenges about doing scenes with that type of equipment?

JH: There are particular muggers who carry out orders of others in Korea. They use those kinds of tools to control people. One day, there was an event that influenced the story of this movie: a mugger blasted fire into a woman’s mouth and damaged her throat.

Korea strictly prohibits guns. This movie is a western, but if the characters were fighting with guns, it would turn into a 100% fantasy movie. No possibility at all. I wanted to have some plausibility in the film, so I decided to work with the tools that these muggers usually use.

I shot double the number of nail-gun scenes that end up appearing in the film. But it made the main character seem too violent, so I deleted half of them.

The last fight between Chul-ki and Ghost Face (Gyee-myeon) is the most important part of the film, so I tried to make the rest of action scenes less violent.

Also, when Chul-ki killed the AX, the fact that he is killed by the amulet which he was always attached to was more important than the manner of killing itself.

I incorporated the back stories into every action scene. Making the audience think of Chul-ki’s sadness was more important than the action itself.

We used a real ax in the film. We couldn’t make the fake ax, so we used a real one, which is very heavy and sharp.

When we shot the scene in which AX tries to kill Chul-ki lying down on the ground using an ax, it could have been a major accident. Mr. LEE refused to shoot the scene anymore because it was too dangerous. He felt threatened.

So the action choreographer make-up director and Mr. LEE tried to make a fake ax midway through shooting. It was made of PVC pipes and Styrofoam, but it looked really good, just like a real one. It looked so real that I was so surprised and felt guilty for the actors because I couldn’t think of making one at the beginning.

As a result, we could make a strong scene using that model. Thanks to their passion and affection for the film, we could get great results.

Q: The movie tells a very straightforward revenge story, but you also incorporated issues of corruption and greed into it - a developer trying to force people out of their land to build something more profitable. How did you decide to make this part of the story? Was it an issue of particular importance to you?

JH: I think I already gave you the answer to this above. Korea has developed very rapidly, so people these days are living in more prosperous and convenient times. On the other hand, people in this society just keep going without consideration for others who are isolated and ignored.

This movie is fictional, but it also points out some of the problems in this society.

Just 4 years ago, 6 laborers were burned to death during a fight with policemen in Seoul. The labors wanted to keep living in their area, so they fought with the policemen who tried to remove them. However, it caused too much harm. This was a very violent event, but a new building was constructed on the spot where it happened. And people seemed to have forgotten the event very fast.

Gangwon province has such a beautiful landscape and great natural resources underground, so similar things easily happen. The people who have lived there are kicked out, and developing facilities are occupying those places.

I started developing this film with the idea that among these many victims, there might be a personal story about one individual who tries to get revenge. This movie is for entertainment, of course, but I thought that it could gain the sympathy of the audience as long as it is based in reality.

Also, it addresses the eternal theme of the ‘revisionist western’.

Q: The ending has a somewhat serial-like feeling to it? Do you have interest in developing a sequel? If not, what type of project are you interested in taking on next?

JH: You’ve got the idea correctly, but I don’t have a plan for a sequel. When the main character ‘Chul-ki’ disappeared at the end, I hoped he wouldn’t get into any more trouble afterwards.

However, I have a plan for a bigger western movie in the future. The time of the film would be further in the past. The background would be the era when the train railroad was constructed for the first time in Korea. The ‘Mr. No Name’ will appear again and he will fight with a harsher enemy.

The project I am currently working on is a horror film. I will bring forth a great horror film with lots of blood, mixed with action and adventure. Please don’t miss it!

For some New Yorkers a few months back,a mysterious loner rode into town amidst the circle of covered wagons that is the New York Asian Film Festival, bearing a heavy burden and carrying thoughts of revenge on the brain. It came in the form of new Korean director JI Ha-Jean’s minimalist and modern Western film venture, Bloody Fight in Iron Rock Valley. While the dust cloud its screenings kicked up was a modest one, the film made a huge impression on me by cutting out all of the excess and in effect distilling a very tight and engaging sequence of violence and leaving the rest up to audience’s imagination.

The film finds the archetypal loner, released from a lengthy prison sentence, in pursuit of a murderous gang of thugs. Their actions are brutal, but little more than those of Chul-ki, who manages to learn about their whereabouts after interrogating an isolated member of the gang.

As Chul-ki rides a motorcycle across a barren landscape on a course determined to end in violent confrontation with those that have wronged him under still cloudy circumstances, the gang, led by a cooly menacing gangster going by the name of Ghost Face, is engaged in a corrupt plot to move a monk off of his sacred land. With this twist, Chul-ki’s path toward vengeance intersects with a more altruistic one of helping the family, particularly the monk’s headstrong daughter, resist the oppression of these local warlords. However, little changes in his steely expression.

The successful coming together of masterfully conceived elements on a quite obviously low budget is a marvel (I was so impressed that I reached out to director JI Ha-Jean to share about how he made it happen, the details of which will follow soon in an interview with him). There is the setting, first of all, which has enough hints to reveal that it happens somewhere in modern times, but is otherwise hazy. The town where most of the action takes place, which seems to be nestled in a mountainous region, contains natural beauty, yet at the same time has a grey tinge of industrial failure. The wardrobe of mostly modern day and casual attire might strike an odd chord at first, but after a bit, it just blends right in with the relative timelessness of the movie. A gently rolling soundtrack of a repetitive bass melody is unobtrusive, but keeps us propelled forward toward the rising action. Fights themselves are riveting, for both their skillful execution and also the use of an interesting array of weaponry, which includes an axe and a nail gun. Yet for the most part, the mood is one of being dangerously on the edge while awaiting the explosive consequences of confrontations long built up. Indeed BLOODY FIGHT...is an exercise in tightly wound coiled spring suspense and its ability to maintain that tension throughout is impressive. This is helped, in no small part, by a cast of characters with a knack for emoting with a little more than an expression. Leading the way is LEE Moo-saeng, whose eyes portend an impending doom.

BLOODY FIGHT IN IRON ROCK VALLEY has not been released in the US yet, nor am I aware of any impending plans this to happen. Seekers of smartly made action films, however, should keep an eye out for both the movie and its very promising director.

Please check back within these pages soon for an interview with director JI Ha-Jean!

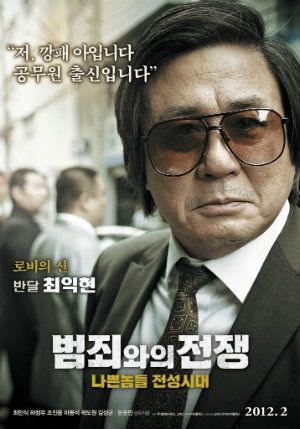

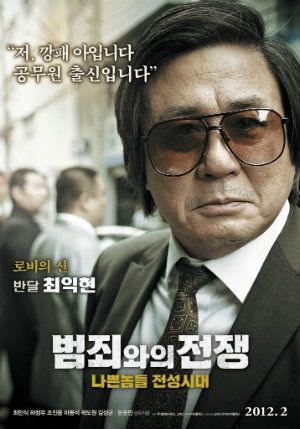

1990: A roundish, eager to please looking man who is well into middle age sits behind the bars of a prison cell. A shrewd looking district attorney, unimpressed with his pleasantries, demands a statement of all of his wrongdoings over the course of the past decade. Rewind to 1982, this same man, though more diminished in appearance, patrols the local harbor as a customs officer. He and his cohorts make a regular practice of skimming profits, taking bribes and other pocket lining elicit activity until one evening, during an inspection, he and a colleague come upon a huge quantity of coke. Sensing that they are in over their heads but unable to turn away the huge potential financial rewards, they seek counsel with the neighborhood gangster to put the drugs in more capable hands while at the same time ensuring they receive a cut of the action.

We go on to see the events before, after, and between these two points, that relate to this often harrowing trip from one to the other. The escapades of the not quite nameless gangster, Choi (so named directly after the leading actor portraying him, Choi Min-sik, an act of tribute on the part of the director), might have ended right after the drug sale if not for a cursory connection between the customs officer and the gangster by way of their shared family name and a particularly Korean concept of showing honor to those of the same ancestral clan.

So Choi Ik-Hyun, the elder customs officer and Choi Hyung-Bae, the younger gang leader form an awkward connection dancing around the tangles of traditional ancestral hierarchy and the more practical rules of respect for those above the law. Their relationship takes center stage as it weathers the storm of rival gangs, international prominence, political turmoil and police crackdowns. Ik-Hyun is too shrewd to pass up the opportunity to make a fortune and too proud to abandon his involvement when things become dangerous. Hyung-Bae also comes to like having the older Choi around; he sees in him both an approving paternal figure and at the same time someone in awe of his prowess.

As time progresses, the balance of power shifts in some ways. Ik-Hyun’s penchant for making and maintaining high level contacts, or greasing palms if you will proves to be an asset to Hyung-Bae’s organization. Especially during this time when maintaining one’s freedom in the face of guilt has as much to do, if not more, with having the right connections as an airtight defense. Soon Ik-Hyun fashions himself a powerful player, instructing Hyung-Bae on proper etiquette among highly influential officials. While not without its perks, it’s an uneasy fit for the more traditional gangster and an odd play for power continues to pervade their tenuous relationship.

Despite his rise in the ranks, Ik-Hyun is never a true gangster no matter how hard he tries. Early on Choi puffs out his chest at the local casino with a karate instructor soon to be younger brother-in-law in tow for security, another character who gets way more than he bargained for. Yet, he is genuinely surprised, hurt even, when the a rival gang’s leader laugh off his proposal for a more equitable arrangement with the casino owner. A stubborn idealism on Ik-Hyun’s part even finds him dealing with that same rival gang leader later on, feeling that he’s earned the right to do business as he sees fit. The trouble it lands him in with Hyun-Bae finds the disheartened gangster empty of bravado, instead seeking pity for his misstep.

Choi Min-Sik’s masterful multifaceted performance captures our attention throughout these proceedings. Before the film is over he will cower, boast, negotiate, and grovel. There is also the split between his gang activity and family life. Brief snippets appear throughout, in which he welcomes his younger sister's suitor to the family and nags his son to keep up his studies. Few actors can pull off such a seamless transition from one mood to another.

Besides Choi Min-Sik, at least two other individuals involved in the movie should receive strong praise. One is director Yun Jong-Bin who, with only a few feature productions under his belt, took on this rather epic project. Not only are there many plot intricacies to keep track of, but also a historical context that demands careful attention. Yun depicts signifiers of the time with the same aplomb that Fincher brought to Zodiak. Music, for instance, is cleverly used to mark the timeframe of the story with the government crackdown of the ‘90s set to a suspenseful score (think the moody beat driven sounds of movies like The Yellow Sea and The Unjust), and ‘80s Korean fuzzed out rock and early pop punctuate the gangsters’ rise to prominence. Bridging the two modes is a cover (by Chang Kiha and the Faces) of a psychedelic pop tune, I Heard a Rumor, with organs even more swirling and fuzzed out than on the original.

The other is Ha Jung-Woo who plays Hyung-Bae. He is an actor that has building an impressive resume of his own, playing complex emotionally challenged characters. See his work in such films as Time, My Dear Enemy, and The Yellow Sea for an idea of his impressive range. Here he gives a great turn as a stone faced gang leader with subtle cracks in his facade that indicate his weakness for Ik-Hyun. His scenes with Choi Min-Sik show off an electrifying chemistry, especially during a frantic final confrontation.

On a few points, Nameless Gangster reminds me of aspects of The Wire. Considering that show’s reputation as a highly realistic crime drama, that comes as a compliment. First is the interesting resemblance between Ik-Hyun and Season 2’s Frank Sobotka, himself a dock worker, who finds himself in a position where crime pays too much to turn down. Both think of their families as they head down channels that bring them closer and closer into conflict with the law. More pointedly is the split between a new and old type of gangster. Both dramas focus on traditional gangsters, like a Hyun-Bae or Avon Barksdale, who grow disinterested, threatened even when the business end of their game comes to take a more dominant role in the enterprises they have established.

When the movie reaches its conclusion, we come to a distant present day, in a scene that speaks of the passing of time from one generation to the next. It does feel very much like coming to the end of a hard travelled journey. One that has spanned years, political change, and personal trauma.

The easiest way for me to sum up The Doomsday Book would be as follows: two world end disaster comedies book ending a somber meditation on our awkwardly progressing relationship with artificial intelligence. Made up of three films, the first and last by Im Pil-Seong, and the middle by the maverick genre contortionist Kim Jee-woon, it offers a rare venture by Korean cinema into the realm of science fiction, with visions of the future that are alarming,thought provoking, and some would argue not too far off.

The easiest way for me to sum up The Doomsday Book would be as follows: two world end disaster comedies book ending a somber meditation on our awkwardly progressing relationship with artificial intelligence. Made up of three films, the first and last by Im Pil-Seong, and the middle by the maverick genre contortionist Kim Jee-woon, it offers a rare venture by Korean cinema into the realm of science fiction, with visions of the future that are alarming,thought provoking, and some would argue not too far off.

The first story, Brave New World, takes a stab at the zombie genre. Here zombie epidemic is linked to gross mass consumption, disposal and the spread of germs and contamination that come about as a result, making it a far more tangible threat than other more fantastical versions have shown. There is great attention to creating visuals that are both comic and stomach churning, as scenes of overflowing trash containers, a cattle slaughter house, Korean bbq dining, and even facesucking kiss causes many of the senses to bristle.

The film starts out with a joke-y sitcom vibe before shifting towards more panic stricken epidemic mode, as the rabidly violent infected citizens begin to twitch into undeadly activity, including the main character, a scientist who’s been left at home to babysit the family apartment. But tongue remains planted in cheek throughout making this story an entry into the realm of zomedy. There is cutting satire, characteristic of Korean films, especially when a live news broadcast of politicians and assorted experts weighing in on the crisis is shown. Even in the absence of infected attackers, nobody keeps their head, as the show devolves into screaming, propagandizing, and Russian folk songs.

There are rousing scenes of destruction and human carnage, much of it shown in the club district Hung Dae, with still uninfected drunken revelers being hard to distinguish from those that have transformed. While this and the satire make things fairly entertaining, there is some loss of engagement when the spectacle of society’s demise replaces any human drama. We’re left with some exciting visuals, and a hint of deeper meaning, but little else before shifting to the next story.

The middle piece, The “Heavenly Creature” is the most philosophical of the three and the only one that I feel fans of ‘hard’ science fiction will find legit. It is a minimally told exploration of the idea of artificial intelligence surpassing its intended function of unquestioningly carrying out humankind’s commands. Readers of PLUTO, Urasawa Naoki’s excellent manga re-envisioning of the Tezuka classic ATOM, will appreciate this for delving into similar territory, looking at opposing reactions to an evolution of consciousness within one of our own creations. There are those that are open minded and sympathetic while others are fearful and suspect of malintentions.

This story takes places at the earliest stages of such kind of potential robot revolution. Here, though, the sympathetic side is represented by a group of Buddhist monks who believe they may have found the embodiment of Buddha within one of their monastery’s worker droids. After a technician called to the scene is baffled by the robot’s complexity of responses to a routine battery of tests, the opposition enters the picture in the form of the robot production company’s wheelchair bound CEO and a team of armed soldiers.

What follows is a growingly intense conversation between the executive, the monks, the robot, and technician, who finds himself in the pivotal point between the job he is familiar with and a developing empathy for the creations he has been working throughout his career. The question remains: should this abnormally functioning robot be classified as transcendent or defective?

Aside from the monastery, the story’s only other setting is a cold, cubicle-like apartment complex where the technician lives and experiences an instance of humans’ growing inhumanity, as a young and unmannered woman demands he repair a robotic pet only to callously dispose of it when dissatisfied with the results. Within this simple story an impressive number of themes abound: the aforementioned question of how to respond if our technology achieves equal intellectual footing, human’s growing attachment to and immersion amidst non-sentient robotic companionship, and the notion of spirituality being an exclusively human quality. On this last point, the film quietly raises an astounding ‘what if’...: What if an android could flawlessly embody and deliver religious sentiment the same if not better than an ordained priest or minister could? It is striking the way the modest tenets of Buddhism match with robot’s minimal expression and appearance.

The confrontation also calls to mind paranoid notions of large corporate entities controlling government and military complexes, to an end that seems more of a risk to our freedoms than that posed by artificial life forms. Indeed this minimalistic venture from the very talented Jee-woon provides much to think about.

For the third and final piece of this trilogy, scientific explanation is out the window. So too are any philosophical ponderings. Once again, this is a humorously rendered tale with catastrophic results directed by Im Pil-Seong. This story plays for bigger laughs than the first, putting earth as the destination for a giant, hurtling something (best left as a surprise), which was unwittingly ordered by a girl killing time on the internet. The televised response to the ensuing end of the world is hilarious, pitting infomercials for rapidly conceived of and very faulty products delivered with rampant enthusiasm versus newscasts run by a dull and listless anchor. This broadcast devolves, like in the first story, but this time it falls into a more universally understood soap opera that plays out among the self-absorbed broadcasters. This film is less about the public falling into a panic and more about the charming persistence of the Korean family unit, but this story really doesn’t sufficient time to develop this theme to any great effect.

While there are many good ideas throughout this trilogy, a few things don’t sit well with me. The fact that the first and third parts are so similar in theme and structure, yet the middle piece is so different might have came about effectively, but to me it made everything feel like it dragged on longer than it should. Had there been some effort to cleverly transition from one story to the next, I might have felt a stronger reason for them all to be packaged together. I might’ve forgiven the disparity more if Jee-Woon’s piece was more interesting. While effective, I found it did not reach the level of awe I associate with just about every feature film I’ve seen him direct.

A different setup would have given the collection some symmetry. If it was three completely different visions, each piece might stand more powerfully on its own. Instead, the Jee-woon directed middle piece made me feel more like I was being taken out of the mode of the first two stories. Alternately, three cohesive stories that all shared a common thread would have been successful as well. I’m reminded of an independent science fiction triptych from 2003, Greg Pak’s Robot Stories. Shot on a very modest budget, each story (all of them directed and written by Pak) stood on its own as unique, but shared similar themes and aesthetics with one another. It gelled together without seeming so disjointed. For Doomsday Book, then, could Im not have put together 3 stories of flashy apocalypse scenarios? Might Jee-Woon’s far more “The Heavenly Creature” have better fit another assemblage of short films, or perhaps stood on its own? Reports hold that the final piece was completed to make up for another director’s short film that could not come to be, and was collaborated on by both Im and Jee-Woon. However, while it does have something of a tacked on feel, it really doesn’t bear much of Jee-Woon’s mark either.

A part of me laments that such great ideas were not worked into something that was molded into a more cohesive whole, one that could have made the same heavy impact as other films that have born Jee-Woon’s name. Still, there are few trips to the cinema that offer zombies and spiritual robots, outlandish visions of world destruction and serious contemplation, in one sitting. This makes Doomsday Book at the very least worth skimming through.

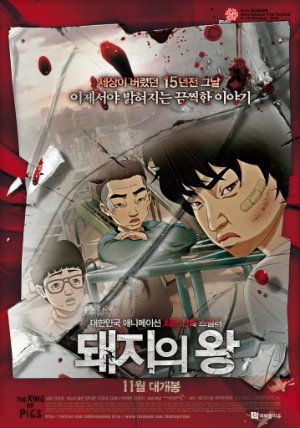

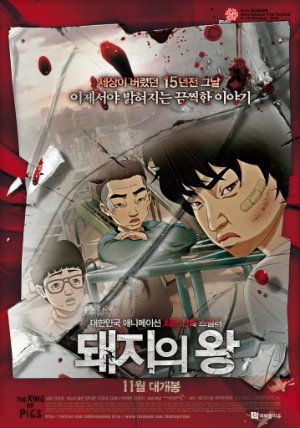

If you’ve ever read a review of a Korean film by me or anyone else, there is a good chance social commentary works its way into the picture somehow. Rarely does an action or drama come along that doesn’t incorporate something critical to say about the institutions in place or the way people treat one another. Perhaps this is why it has a voice commanding so much attention among film enthusiasts worldwide. Yet rare is the film that so completely serves as a statement of social commentary as The King of Pigs. The first feature film by Yeun Sang-Ho, The King of Pigs is an animated tale that rips the lid off of a system of abuse reportedly common in South Korea’s jr. high schools.

The King of Pigs is a thoroughly independent production. It comes after only directing animated shorts prior to it and according to Yeun in an interview I did with him, he started working on it before receiving any funding, only later receiving a 100,000 dollar grant from a company that invests in independent films. Most of those involved in the film’s production, including the voice actors, are from among the directors friends. He describes how he worked with Yang Ik-June and Kim Kkobi (familiar to many from their work together on the film Breathless) because he “had talked to them a lot about this film beforehand....It was more of a collaboration for fun rather than calling it casting.”

It begins in an almost impossibly bleak place: a woman lies dead, strangled, as a distraught man trembles in a shower. The bespectacled man, calmer now, receives a call from an investigator with the contact information of a former classmate whom he quickly makes arrangements to meet. That man is Jong-Suk, a freelance writer stuck in a clearly unfulfilling assignment. Distrustful, or just filled with pent up rage, he lashes out physically against his live-in companion after she returns home late without returning his phone calls. As low and damaged a state the two former school friends find each other in, signs point to an even darker past, which comes up through episodes they recount in one particularly tragic jr. high school year. It offers insight into the roads that may have led them to these malcontent grown up lives, and is the first of many allusions to continuous cycles of violence and despair.

Flashbacks show an all boy school as a frightening place for many, who are subject to the whim of a few. Classroom ‘managers’ taunt and order around the more meek students in the class, giving approval to certain acts of bullying while menacing others for their lack of seriousness in their studies. They do this under the watchful eye of an upperclassman who beats them should they fail to maintain a positive environment in the classroom,and he in turn reports to an older student who is something of a leader in the school government. This hierarchy of overreaching control is not made up of embittered underachievers or those who are victims of abuse themselves. Rather, these members of the school community appear to be economically advantaged. As a result, they also experience academic success making for a reinforced achievement for some while for the majority, failure perpetuates itself. An incensing scene finds the class monitors tormenting a talented boy to the point that he relinquishes a venerable spot in a writing competition to one that is accustomed to receiving every accolade. adults are eerily absent from the picture or at best very slight in their influence.

Jong-Suk perceives these different types as dogs and pigs. The dogs growl menacingly and control what goes on while throwing scraps to the pigs who can only hope to have occasional kindesses bestowed upon them instead of the usual abuse. As if in answer to the state of fear these students live in, another crucial character, Chul, appears.

Chul’s homelife is the most unstable and perhaps as a result he is reckless enough to defy the bullies. While another key figure, Chan-young (the same whose opportunity to enter a writing contest was dashed) tries to escape the fate of the pigs by putting his head down and trying to outlast the abuses of the class managers, Chul matches violence with even worse aggression. His message is not that of taking a higher road, but rather one of becoming a bigger beast than those who would behave monstrously. Despite his scary demeanor, he represents a fighting resistance against those in power to Jong-Suk and Kyung-Min. And yet, his propensity for greater violence brings adult authority down on him and leads to confrontation with the highest level of students running the show. The only act left for him to conceive of that could make a difference for the three is so desperate and fatal an idea, it seems destined to fall into ruin.

Meanwhile, the causes for such disparity between students are shown to extend beyond the confines of the classroom. In the young Jong-suk’s family home, his sister throws tantrums about her lack of up to date goods that others around her enjoyed. She even turns to theft to compensate her frustrations, which are amplified by a status-obsessed society. Students speak of the long stints of time they go through without being able to afford to eat meat. In a poignant exchange, Kyung-Min finds his father, an only relatively prosperous owner of a karaoke bar and the elicit prostitution that takes place there, violently casting out Chul’s mother, whose impoverished state forces her to take on this undesirable work. Chul is there too, ready to strike out to defend his mother, but the sight of Kyung-min causes him to leave in despondency. It shows how even their bond of solidarity in class is tainted by the venomous relationships that have long been poisoned by want and squalor.

While animation brings to mind fantasy, there are strikingly realistic aspects of this story. Instances of bullying, like when those that wield influence question an individual’s sexuality threateningly for failing to abide established fashion codes, will seem familiar to anyone who’s experienced or been around others who have experienced middle school taunts. Also resonating a recognizable truth is the way bullies conspire to administer sly cruelties until the put upon individual finally lashes out in more serious violence, only then bringing the attention of adult authorities to come down on the one who had been victimized. Perhaps this great realism owes to the fact that, according to Yeun in our interview, “individual episodes in the film are based on (his) experiences” although “structure wise the (story) is pretty much fictional.”

Animation then serves to drive some of the cruel aspects of the story home vibrantly, if not exactly entertainingly. There are fantastical transformation sequences: humans transform into dogs and swines to represent their status. Chul, a boy from whom violence is inseparable from existence, warps into pitch black monstrous forms to show his increasingly hate-filled state of mind. Sequences of a wild eyed cackling feline (perhaps meant to be viewed as the spirit of a cat that was killed in a ritual of brutality) and corpses of deceased family members taunt Jong-Suk, showing the tortured states of mind they are in over their powerlessness in the face of more well-off bullies.

The look of animation also suits the fable-ish nature of the story with its animal-based allegory on haves and have-nots. In fact Yeun claims being a fan of all types of animation including Disney. Chul’s sudden appearance and ability to vanquish the villainous tormentors in the class makes him a mythic figure. Yet, fantasy comes crashing into depressing reality. His heroism comes from a dark place, one brought about by earthly hardships of family tragedy and economic plight. This along with the social politics of school life prove insurmountable.

As Jong-Suk and Kyung-Min continue to recall their harrowing younger days, it becomes clear they are skirting around something. A tragedy with jolting and fearsome connotations will come to light, revealing opens wounds that have never been healed.

The movie may be considerably remarkable movie fans in the West where relatively few South Korean films on this subject have surfaced. In fact they are out there. Yeun mentioned over movies that take on the subject of school bullying, such as Our Twisted Hero. His film stands out, however, as Yeun “didn’t want to fall into that kind of convention, but instead look at (the issue) from a different perspective.”

The lack of simplicity, of an easy to follow struggle between clearly defined hero and villains, helps make it a powerful vision. It also reflects Yeun’s views on the real-life problem. When asked, for instance, about the lack of adult presence, he answered: “In Korea parents really do work a lot. They don’t have much time to spend with kids. I think it’s more of the Society’s problem, not the parents’ responsibility but the society that drives parents away from the kids and into work.”

In fact the film often straddles a line between genre film and more unconventional project. Setting the film’s dark tones from the outset is an ominous-sounding score. Yeun mentioned how he asked the music director for “the soundtrack to be in genre convention. And also (being) a big fan of the soundtrack of Twin Peaks by David Lynch wanted something similar to that.”

While offering little in the way of solutions or hope, The King of Pigs is a piercing beacon shining light on a situation that should be looked upon rather than left to fester in the darkness.

Before the 2012 New York Asian Film Festival crashed the summer, bringing with it Choi Min-Sik and an impressive host of his movies, a concept was established: The Violent Eye Party. While none too clearly defined, here are some of its proposed tenets:

- movies from the back catalogue watched in marathon-like progression.

- movies picked, ahem “curated,” by one of the Violent Eye’s rotating collective, with a theme in mind,and if possible, an international scope.

- comparisons, connections welcomely explored.

- focus on and appreciation for portrayals of violence in movies, primarily (for the time being at least) Asian.

This is a report on the first Violent Eye event, which took place before attention and activity turned to Choi-Min Sik’s films and his appearance at NYAFF 2012.

This first set of movies was the preferred triple feature programmed by the Violent Eye’s resident conduit to the physical world, Mondocurry. Its theme, or at least attempted theme, was one on one showdowns. The movies shown were LIKE A DRAGON (2007), THE CHASER (2008), and DOG BITE DOG (2006). They came from Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong respectively.

If there was anything that proposed a challenge to the theme (hence the ‘attempted’ remark earlier) it’s Japanese cinema. The genre pool is filled with movies flying the masts of horror, sexploitation, and Yakuza (gangster) dramas. The last of these was surely the most promising to select from, but mostly involve drama and to-be-expected complex interactions between various characters of different rank and gang affiliation. Fight choreography is often a minor feature. (Should you, reader, have any fitting suggestions you feel was missed, please do share them). And so came about the odd choice of LIKE A DRAGON, a Takashi Miike adaptation of a Yakuza themed video game. That Miike’s name came up is no surprise, as he seems a director most readily associated with contemporary Yakuza themed action films. One of the considerations for a different Japanese film was one of the three parts in the quite uneven Dead Or Alive trilogy, which he also directed.

Yes, LIKE A DRAGON did promise a showdown: On one side, recently released from prison gangster with a heart of gold, Kiryu Kazuma, and opposite him, erratically behaving gang boss Majima Goro, whose knowledge of Kazuma’s release registers a remembrance of some kind of grudge that bears repaying without wasting a single minute. Before you strap yourself in for a fast-paced back and forth battle, know that this situation is surrounded by at least four others (some connected and some not), and bounces between them with a severe case of attention deficit disorder.

The fights between Kazuma and Majima are frenetic, but bear a tone of silliness. Perhaps owing to being in “video game mode,” Miike chooses to embellish battles with cartoonish effects (fast spinning bats, neon electric charged “power up” punches). It does make for some fun. Majima is quite a colorful caricature of a villain, patch on one eye, carrying a golden baseball bat which he uses to bash away liberally at rival gang members and one of his own lackeys. The Warriors-inspired concept is taken to cartoonish heights as Majima tosses baseballs into the air only to smack them at the targeted heads and abdomens of his opponents. As conclusions draw near, a hotel battle between the two finds Majima batting baseballs that ricochet from wall to wall at an angered Kazuma. With Majima, Miike also takes a page from “exhaustion action” trends, with the patch-eyed slugger fairing worse for wear in all of his battles with Kazuma across a neon imbued Tokyo; yet, he continues to drag himself off the floor and stagger to the next battle. Meanwhile Kazuma is all righteous indignation-fueled strength that has him convincingly (with a little suspension of disbelief) fending off hordes of gang members singlehandedly.

Whatever the source of their beef, the battles between the two never go beyond surface level aggression. As for the other goings ons, they range from a pair of incompetent robbers holed up with their hostages in a bank, a girl and boy on an impromptu crime spree with an incident from the girl’s past looming over their heads, and a Korean assassin who is targeting a major criminal organization for unclear reasons. Meanwhile, when not fending off Majima’s attacks, Kazuma is helping a little girl to find her mother who is somehow wrapped up in said organization. Miike successfully creates an atmosphere where an Indian summer has everyone itching and squirming and making rash decisions under the pressure of the heat. But all these loose threads hardly come together into one coherent package. The ending explosion leaves a giant question mark hanging in the air. It may be a successful adaptation of a video game, but its way of operating does not come close to translating into narrative logic. Along the way are some other hallmarks of the typical Miike-helmed Yakuza film that make this fail to stand out from the rest of the pack. One is the inclusion of 80s-like squalling guitar solos throughout the movie. For whatever reason, Miike has chosen this many times over as the sound of modern gang conflict suspense. To me, it is more of a distraction than a mood builder. While the movie does take some impressive strides toward combining intense action sequences with a gang related drama, it draws attention to a definite demand for new voices calling from the director’s chair to add some diversity and maybe even a little one upmanship into this genre.

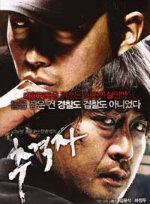

Considering the order the movies were watched in, having THE CHASER in the middle position, we could liken it to the main course. It fit exactly what was being sought: a story of two individuals trying desperately to destroy one another. The mood is consistently grim as director Na Hong-Jin unfolds a tale of bad vs. worse -- a disgraced cop turned prostitute tracks down a trail of missing prostitutes to a detached serial killer. The pimp, Joong-ho is as reluctant a hero (if such a term can even be used) as one could find; his attitude about the girls’ disappearance is filled with cynicism, at first insisting that the missing girls had run off with money he is due. When the truth comes to light, his drive to take down the elusive Yong-min stems from a combination of seeking comeuppance for trouble caused, the slight bit of redemption that will come from saving the last girl to disappear with the murderer, and sheer stubbornness in the face of a police force who are tied up in political games to the point of complete inefficiency.

The story is more about Jong Ho and a dysfunctional police force’s pursuit of Yong-min, while meanwhile, he wants primarily to escape and continue his murderous ways. Their final exchange is a nasty,artless tumble, including attacks with a hammer and chisel and bodies hurled into fish tanks. Leading up to it is an awkward suspense of missed opportunities and local naiveties that conspire together to make Murphy’s law that anything that could go wrong will go wrong come to life. It not only kicks, but stomps down repeatedly on the audience’s gut.

Characteristic of many dark Korean films is a strong voice of social commentary and the ability to summon gallows humor in the midst of even the most terrible situations. A running gag on cell phone tags leads to the ensnared prostitute’s daughter referring to -- as he is labeled in its memory: filth. What stands out in this all around masterful first feature for the director is the dynamic between Jung-ho and Yong-min. Jung-ho is all red hot rage and bluster to Yong-min‘s ice cold, near impenetrable demeanor.

The two leads, Yun-seok Kim and Jung-woo Ha would later trade roles of vice and relative virtue, appearing opposite one another in Na Hong-jin’s second feature, The Yellow Sea. While a less perhaps a less perfect battle than the one found in CHASER, that film’s scenario of an individual brought into a metropolis from a nearby economically disadvantaged country, thereby wreaking havok on, and in effect destabilizing a more advanced yet corrupt society mirrors what happens in our third feature, DOG BITE DOG (directed by Pou-Soi Cheang).

In an alternate universe of my devising, instead of being famous for a computer filled with photos of sexual exploits, lead Edison Chen would be most recognized for his ultra aggressive turn in this film. He truly captures the essence of the mad dog killing machine archetype. In one very quick and efficient setup, we find Pang (Chen’s assassin) whisked across the sea from Cambodia towards a high society target whom he instructed to put a bullet or two into. In a fast and bloody scene of jolting adrenaline, he dispenses with his (somewhat disturbingly) elderly victim, turning his attention thereafter to evading the local cops and making his way back overseas. His every action is about survival -- from using his hand to shovel handfuls of food into his mouth to pushing back the police using hostages whose lives only last as long as it takes him to grab the next one. In keeping with the tradition of its Hong Kong action predecessors, the story does not dwell much on plot intricacies. Little is made of the reason for the contract killing. Rather, we follow the fugitive as he escapes to a junkyard of fetid towering heaps of trash where he finds a girl living a secluded life of abuse at the hands of a repugnant father figure. Pang frees her from this reality making the two allies in a bid to escape to a Cambodia that now seems less savage than Hong Kong with its corruption and people abusing power. From here, instead of worrying only about himself, he has a vested interest in protecting this girl, who in turn becomes something of a leverage point for the cops in pursuit.

The assassins nemesis comes in the unlikely form of Sam Lee (an actor who appears in many actions films, but rarely as the lead) who plays Inspector Ti Wai. The combination of family drama in the background -- his father, a troubling combination of inspiration and disappointment having been charged with drug related corruption is hospitalized -- and the cold blooded efficiency with which his comrades are maimed or killed leads the young police officer on an obsessive course towards bringing in the killer or annihilating him in the process.

There is a point in the film where it could have ended somewhat elegantly and with a contemplative image left to sink into our consciences, if not in the most conclusive fashion. However the film insists on going forward, beyond restraint or good taste. Like the film’s introduction, a flash forward to Cambodia begins and speeds through significant events like a ticking bomb is strapped to its back. The couple, thrown together by a struggle-filled fate,settle down with an expected child and a life free of violence. Then, in a move that is just shy of defying time and space, Detective --- appears, transformed, having put himself through the trials of a brutal underground fighting ring. Things spiral quickly into a violent climax with a tragic turn of events.

The film does leave us with a final, striking image but this one is meant to shatter. Like in CHASER, the intent is to leave jaws dropped and emotions drained. It may have done so more effectively if the final stretch was not so far fetched a turn of events, but the Cambodia sent the movie straight over the rainbow. Even sonically...In the background of the final battle (taking place among beautiful temple ruins) a syrupy rendition of the song ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’ plays, which sent the New York Asian Film Festival audience with whom I first watched it into unintended fits of laughter. It clearly did not have the intended dramatic effect on Western audiences who are too familiar with the tune. Beyond that, the director was trying to make a grand statement but it ended up as overkill, since the images of what happened were sufficient enough in driving its message of cyclical violence home. This film has some of the most tightly wound fast paced action sequences around. It could have gone down as a tight suspenseful exercise in violence, and for most of the film it functions as just that. But the over the top ending will probably have it going down in most memories as an overblown attempt at social commentary.

While South Korean and Hong Kong cinema both have a wealth of talent dedicated to portraying physical action, Japanese productions don’t offer it as much or perhaps there is just more interest within the serious film market in horror and drama. Most of the Japanese movies that come to mind with a major focus on action are from Miike and Nishimura Yoshihiro. Both make movies that contain varying degrees of cartoonish elements. While genre director Ryuhei Kitamura comes to mind (with a movie that is perfectly titled VERSUS!) his work was usually centered around science fiction or fantasy and delivered action, but with very little that could be taken seriously beyond the choreography. While this installment’s Hong Kong representative has thrilling action, it was not presented in a way that was conducive to serious consideration of society’s ills. Finally, the South Korean film combined intense action between two compelling individuals with a story that drags several aspects of society through the mud. It’s a film that is hard to watch without feeling devastated afterwards.

Winner? THE CHASER

Some acknowledgments:

Unseen Films for inspiring me to document my impressions on film and providing me with a respectable home from which to do so.

Planet Chocko Zine with its intensive reporting on all things rising up from the underground, including (but not limited to) films, music, art, and whose cast of characters throw their support and hats in the ring for intense screening marathons like this one.

CineAwesome whose cleverly titled podcasts on genre film double features are filled with witty banter and an encyclopedic knowledge on cool good and cool bad films. It’s probably more of an influence on the activity here than I’d care to admit.

Your comments are appreciated and will be answered!